So what do people think when they hear the phrase “Curiosity killed the cat”? Do we assume that it warns us of the consequences of asking too many questions? Or does it point to the limited capacity of a brain that can malfunction if it works too hard to understand the world in which we live? Of course, scientists now know that our brain cannot malfunction due to “excessive curiosity”. Here are the reasons why.

1. Your brain is a work-horse, not a store house.

The more you exercise it, the healthier and more efficient it will be. In fact, if you want to really train your brain and increase your intellectual ability, stoking your curiosity about the world is one of the best ways to achieve that.

2. Your brain is not a computer.

In the 70s, the cognitive branch of psychology was dominant and scientists saw all of human development in terms of a computer-based metaphor of a brain as information processor. The information processing approach (see Woolfolk, Hughes & Walkup, 2008) saw the mind as a machine that takes in information, performs operations to change its form and content, stores the information, retrieves it when needed, and generates responses to it. So learning, remembering and thinking involve gathering information, encoding, storage and retrieval. This is a useful analogy in many ways and it makes it easy for people to understand how information might be processed by the brain. The problem with it is that people then assume that the brain actually is a computer, with only as much memory storage or capacity as is available on the hard drive. If the hard drive doesn’t have enough capacity, then you need a new one that is bigger, better or faster. This is a very limiting view of our brain’s capabilities and some have called it a form of “negative psychology”.

3. We don’t know the limits of human learning.

We may never know them. Thankfully, many psychologists have eschewed the notion that our brain has limited storage capacity which is great news for the whole field of education as well as for the curious natured individual. A nice illustration of this can be seen in Psychologist Steve Hayes’ (1993) discussion of Lerner’s (1993) epigenetic approach to human development. Lerner argued that there may exist predetermined genetic limits to human development. But Hayes explained that because we know that stimulating environments can help to make us smarter, there are no limits to our intellectual development until they have been reached. These limits can only be reached through exhaustive attempts to create ever more exceptionally stimulating environments.

4. Scientists have learned a lot by being curious.

We used to think that persons with Down Syndrome would never present with measured IQ scores of more than 60, but now many persons with this genetic condition have received excellent intervention and high standards of teaching in enriched environments and are now capable of attending college. Thirty years ago the only outcome for persons presenting with Down Syndrome when, for example, their families could no longer care for them was to be institutionalised in a state care facility. Now many are living completely independently while others enjoy various levels of assisted or partially independent living and working environments. This only happened because the so called “limits” were pushed by psychologist that did not believe that curiosity can kill a cat. In order to develop the range of powerful educational methods that have enriched the lives of those with Down syndrome, scientists themselves needed to be curious about what might happen if you continually enriched the educational environment of someone with a developmental difficulty. Isn’t this the way all great scientific breakthroughs occur? In the latter example, the curiosity of psychologists about the intellectual “limits” of someone with Down Syndrome actually improved people’s lives. Thankfully those psychologists had not believed the old feline cliché when they were young.

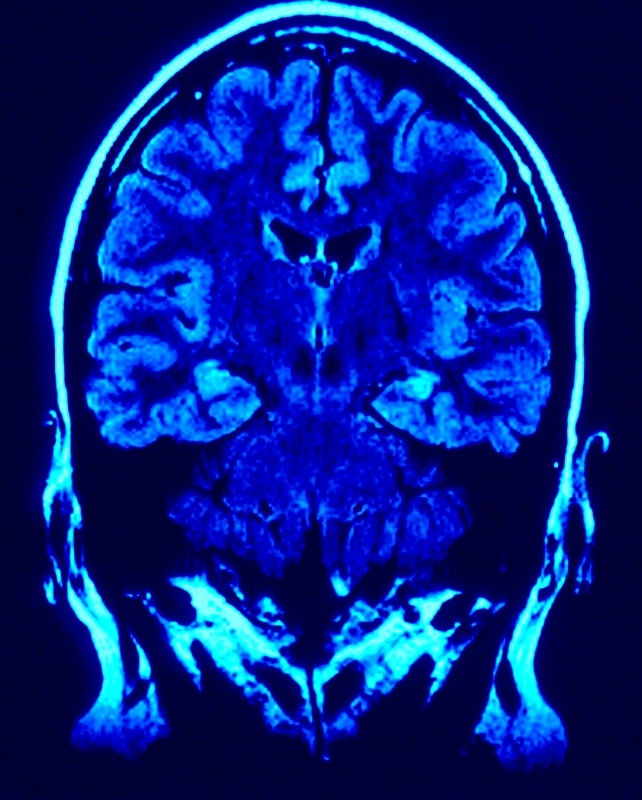

5. Neurogenesis.

Neurogenesis is the stimulation of brain growth. It is the process by which neurons are generated from neural stem cells and progenitor cells. Most of this neural activity happens during pre-natal development, but we also know that it continues to happen throughout the lifespan. It is now a well-established phenomenon and we often hear about it in the context of brain training software used for older adults who may be experiencing some level of cognitive decline or for anyone who simply wants to increase their IQ. Indeed there is much evidence supporting the efficacy of brain training interventions in studies examining its effects on stroke recovery and management of dementia in the elderly (e.g., Smith et al., 2009). Some of the intellectual skills improved by such training are very important foundational skills like memory and attention that had perhaps been quite well developed at an earlier time in the person’s life (see also Ball et al. 2002). The important point here is that the stimulation of specific brain regions through brain training supports ongoing growth and development in areas of the brain which are important for intellectual pursuits.

6. Brain Training has been shown to improve intelligence.

In a groundbreaking 2011 study conducted at the University of Michigan, and widely reported in the media, Susan Jaeggi, John Jonides and colleagues reported improvements in one aspect of intelligence known as fluid intelligence that the researchers achieved for their research volunteers by having them engage regularly in a brain training task known as the n-back procedure. Another research study conducted in Ireland (Cassidy, Roche & Hayes, 2011) reported significant IQ rises as a result of an intensive computerized “relational skills” brain training program. These large IQ increases were maintained 4 years later without any further intervention (see Roche, Cassidy & Stewart, 2013). Both of these studies moved people’s intellectual ability well beyond its assumed limits- without any disastrous consequences for anyone! (For more research in this area visit this site). So it appears that there may indeed be no real limit to our ability to develop our minds. This kind of research pushes the boundaries of what many experimental psychologists and brain scientists thought were the limits of learning.

7. Curiosity can help us to lead more fulfilling lives.

Our brain is naturally curious and as I have argued, it cannot fill up because it is infinitely “malleable” or “plastic”, like play dough. Learning never stops, and we continue to learn and develop across the whole lifespan. One of the key ingredients to keeping that development on an upward trajectory is to nurture your native curiosity. The Psychologist Todd Kashdan wrote a whole book on the topic called The Curiosity Advantage, in which he presents the evidence that our brains are infinitely expandable, and that curious people lead more fulfilling lives. Kashdan is not talking merely about healthy cognitive development, but extols the virtues of curiosity for our mental health and our emotional well-being, too. And here is an important paradox he outlined. Too many of us have been sold on the idea that enjoying ourselves and being happy is the only, or most important, goal in life. But, instead of chasing happiness, Kashdan outlines the evidence that we should focus on trying to create a rich and meaningful life, guided by core values and interests. We can do this by chasing up the things that make us curious in every area of life.

8. Being curious increases our “flow”.

Kashdan’s ideas fit perfectly with what neuroscientists have been telling us about keeping our environments “stimulating”. But Kashdan adds the important advice that by being fully engaged with life, we also derive more happiness from it – as a pleasant by-product. Positive psychologists call this state of total immersion in whatever fulfils you “flow”. The concept of flow was the brainchild of Mihaly Czikszentmihalyi, (1990) who used it to refer to a genuinely satisfying state of consciousness, which is the optimal human experience. You are in a state of “flow” when you are so deeply and effortlessly involved in what you are doing that you forget all else. Flow activities challenge you and engage you with all your senses and all your being. Flow activities are not necessarily enjoyable when you are doing them (e.g., competing in a swimming competition or staying up all night studying) because they really and truly push you to your limits, but the sense of accomplishment you gain from doing them is what leads to you feeling so happy and so positive about the experience in the aftermath.

So being curious is about being engaged with your environment in a deep and meaningful way. It is about chasing the things that interest and stimulate us. It is about doing these things to the best of our abilities. Being curious is not about being nosy or getting involved in other people’s business. Being curious is about increasing our quality of life in all domains. Being curious is a good thing. In fact, it is a great thing.